Invalidation and Infringement: Michael Jordan's Dual-Pronged Offense in China Trademark Battle

May 15, 2020 | BY

Vincent ChowChina's Civil Law provides brand owners alternative avenue for IP protection

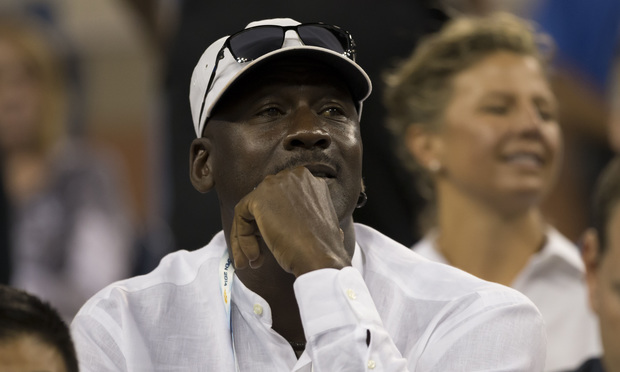

Michael Jordan. Credit: lev radin/Shutterstock.com

The Supreme People's Court's (SPC) March decision in favor of Michael Jordan in a series of trademark disputes against Chinese sportswear company Qiaodan Sports was hailed as a victory for the former NBA star and a milestone for protection of similar marks in China. But Jordan's protracted legal battle in China is far from over. The basketball legend does not just want to strike down Qiaodan's violating trademarks – he wants to bar Qiaodan from using his name once and for all.

The SPC ruled that Qiaodan's registered trademark of Jordan's transliterated name in Chinese characters violated Jordan's trademark rights and should therefore be revoked. The decision marked the end of an eight-year administrative lawsuit in which Jordan sought to invalidate trademarks registered by Qiaodan, a sportswear company founded in 1997, whose name is the same as Jordan's transliterated name in Chinese, "Qiao Dan."

Jordan's victory was only partial with the SPC decision. Out of 78 trademarks Jordan has sought to invalidate, only a handful have been struck down – those relating to Jordan's transliterated name in Chinese characters – "乔丹". The Chinese company's other trademarks, including Jordan's transliterated name in pinyin, Qiaodan, its logo resembling Jordan's famous "jumpman" silhouette, Jordan's jersey number 23, have all been upheld.

This premium content is reserved for

China Law & Practice Subscribers.

A Premium Subscription Provides:

- A database of over 3,000 essential documents including key PRC legislation translated into English

- A choice of newsletters to alert you to changes affecting your business including sector specific updates

- Premium access to the mobile optimized site for timely analysis that guides you through China's ever-changing business environment

Already a subscriber? Log In Now